|

It was mid morning in April 2011. Dubey and I waited at the swank Terminal 3 at Mumbai to catch a flight to Delhi. He was showered and wearing fresh clothes, and was eagerly looking forward to the trip. He had told me before setting off for the airport that he was going to nap during the flight and that on no account should he be disturbed for breakfast. He gave the same instruction to a stone faced CRPF man at security, and again to the airline staff checking our boarding passes before we got on to the aircraft. But when the breakfast tray arrived he was hungry and enjoyed the kheer most. He hailed a passing airhostess and asked her to compliment the people "inside" for the quality of the kheer. She was delighted, but also confused.

Dubey had been awarded the Padma Bhushan, and he wanted me to accompany him to the award ceremony in Delhi at the Rashtrapati Bhavan. He was not well at all. He was troubled by frequent seizures, some of which lasted as long as five minutes, and I was not sure I'd be able to handle a medical emergency on my own. But Dubey was excited, and eager to travel to Delhi. " All of you have become very busy. We've not spent much time together recently. Lets use this opportunity to talk about your ideas and plans for new plays," he said.

|

|

|

|

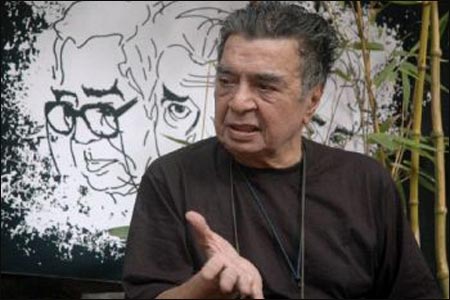

SATYADEV DUBEY |

|

That was true enough. I was not really spending time with him apart from short conversations at the Prithvi Café over a cup of tea, or late in the night after a performance. I often asked myself if I was in fact avoiding being with him. His seizures were unnerving, and frightening, though he coped with amazing will power, often picking up a half finished sentence or thought as soon as the worst had passed. Too often the answer to my own question was, yes, the coward in me was not able to deal with what was happening to Dubey.

When I started working with Dubey I was 17, and we were doing so much work that I think I spent every possible moment with him. This continued for ten years. Either we were rehearsing, or performing, or traveling, or work shopping. After a performance at Chabildas in Dadar we'd walk to my home in Santa Cruz ducking into little bars on the way, while he spoke at length about theatre. Or a few of us would bundle into a taxi and ride to the coffee shop at the Centaur Hotel, and spend the night nursing a beer, topping it up with rum we'd smuggled in. His new flat at Sahitya Sahwas was more of a theatre space than a home. There were books to study, scripts being read, rehearsals, and writing and acting workshops. The bare kitchen, the empty refrigerator, the dusty mattress on the floor had lost the battle to make it a home.

I was only slowly beginning to understand what I was part of. When you are in the thick of the action its not easy to step away and examine the situation objectively. This was Dubey's second phase, his second wind, so to speak. It was 1975. He'd established his reputation in the 60s, and hit a peak by the early 70s, but then circumstances had changed dramatically. He had to give up Walchand Terrace, home to his theatre for several years. Many of his former colleagues had drifted away, or had been pushed away. Some formed their own theatre groups, some simply moved on in life. When I did Elkunchwar's GARBO with him he had only Sunila Pradhan and Amrish Puri as his core group. I had no clue how fortunate I was to get in when I did, because over the next few years he gathered a new set of people around him, and worked furiously on new productions. We were running five plays at any given time, performing at Tejpal, then Chabildas, and when the NCPA complex came up, at the Tata Theatre, Karnataka Sangha, and at the newly built Prithvi Theatre. He directed in Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati, and eventually in English, and his scripts came from writers in Maharashtra of course, but also from Karnataka, Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Europe.

Shanta Gokahle sums it up when she says, "Satyadev Dubey made his theatre in Mumbai the crucible of a pan-Indian, pan-world theatre consciousness by producing plays translated from different Indian and European languages. This cross -pollination gave audiences the first glimmer of a larger Indian theatre sensibility. To date he is credited with directing and producing over a hundred theatre productions in Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati and English, many of which are considered landmarks in modern Indian theatre. The influence of his style of theatre can be found across the country. "

That understanding came much later. We were too busy having fun being immersed in the theatre. Working with Dubey had its advantages - you learnt a lot, and very quickly. There were opportunities to engage in every aspect of theatre; acting, technical, design, direction, production, organizing parties, holding your drink etc etc. Important and well-known people from the arts came to see your performances (Shafat Khan wrote a superb tongue -in -cheek piece about this, and it is reproduced in Shanta's book on Dubey), and you were written about. But there was a downside too. Dubey's enemies - he went out of his way to cultivate them - became your enemies. The new generation of theatre people regarded you as part of the establishment - ironical, cruel even, because the real establishment never accepted him. Your view of theatre was coloured by Dubey's views; the NSD was out, English theatre was out, Brecht was out ... it was a long list of strong prejudices. At first I accepted this as an inevitable par of working with him, but over time I grew uneasy. I needed to find my own equations with ideas and people, and I wanted to work differently with actors, and have plays say what I cared about.

There were opportunities because Dubey created space for us to do independent productions within his Theatre Unit. Akash Khurana, Harish Patel, and I did Dubey's superb translation of Harold Pinter's The Caretaker on our own. It worked well, and we grew in confidence. Then he threw me a challenge and asked me to direct his play, AADA CHAUTAAL, a difficult, autobiographical text. I didn't understand the nuances, but I did it anyway, because that was how it was. You just did it. The opening scene was an introspective monologue on being a Hindu in modern India, and in the period leading up to the religious polarization of India, it made sense to question one's connection with faith. So it appeared as though the immediate crisis of identity had passed.

It came as a surprise when Dubey told us one day to leave, and find our own way. I'd seen this happen to other people, but usually it was after an angry outburst at a real, or imagined, mistake the person had committed. In our case it was calm and firm. "Make your own mistakes, take credit for your success, and responsibility for your mistakes," he said.

This was 25 years ago. The association continued, but it was different. He'd always treated us with respect, but now he smilingly called us his "competition". It was flattering, but also daunting. It was important for me to find my identity in my own space, and so I kept away from him. He has always enjoyed sitting in during a rehearsal, and taking over, unconcerned about the awkwardness it caused to the hapless director, or actors. I never invited him to sit in on one of mine. It did not seem to bother him. He'd slip into the theatre during a technical, and offer suggestions as gently as it was humanly possible for someone like him. He would invite me to run through a newly rehearsed play for students of one of his acting workshop. "An audience response at this point will help you see the play objectively." Always the play ...

By the time we got to Delhi, Dubey was exhausted. He had several seizures on the flight, and the long distance he insisted on walking at the terminal tired him out. He had wanted to go out in the evening and meet some friends. But after a nap he said, 'Let's stay in the room and talk."

It was a long evening, very easy paced and comfortable. He talked at length about the film he had made and was editing, and how he wanted to change the second half. "The first half works, the second half is a disaster. Let's just cut it out." He was resigned to his medical condition. "I am prepared for the end, tell everyone not to worry so much about me."

The next morning he dressed himself with some difficulty but eventually looked very smart and dapper. The clothes made especially for the occasion looked great, and he walked confidently to receive his award. The President of India, Pratibha Patil, presented the award. She was the.Minister of Culture in Maharashtra at the height of the Sakharam Binder censorship troubles in the early 70s. The irony was not lost on him. He smiled, " see how things have changed".

The last months before the end were hard for Dubey. He fiercely guarded his independence, refusing to allow anyone to help him cope with medications, food, travel ... life. All the things we do without a second thought were becoming difficult tasks for him, and with each new set back he became even more stubborn about doing things his way. It was as though he was willing the inevitable to happen on his terms.

*Sunil Shanbag is a well-known director and documentary filmmaker. He has produced and directed critically acclaimed plays under the banner of his theatre company, Arpana.

|